Orientation vector

An orientation vector specifies the orientation of an object in 3D space. You use orientation vectors to specify relative orientations of components when using the motion service and frame system. The first three components of this vector form an axis pointing in the same direction as the object. Theta specifies the angle of the object’s rotation about that axis.

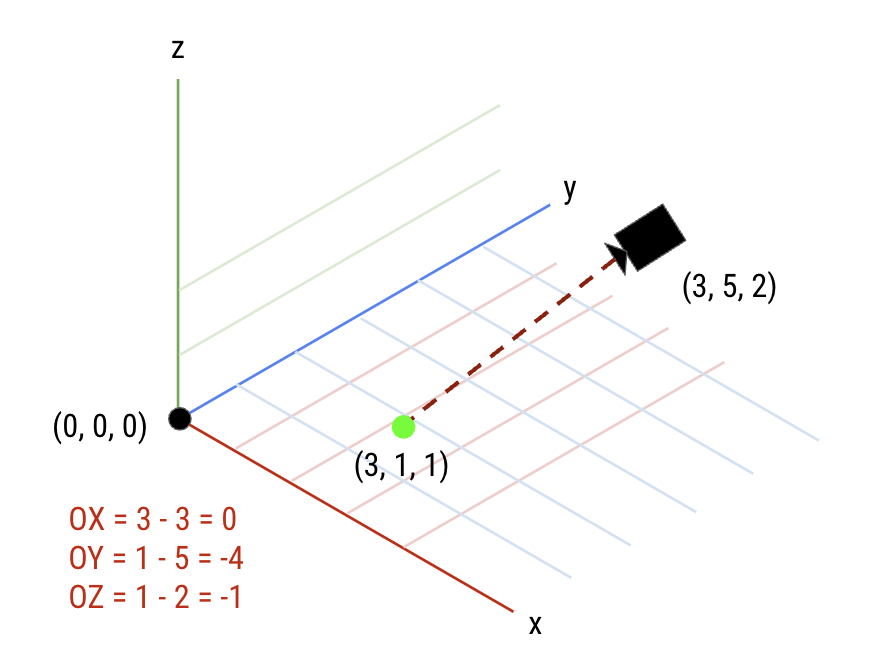

Example: A camera in a room

Imagine you have a room with a camera. The corner of the room is (0, 0, 0).

To configure the camera into the frame system, you need to know where in the room the camera is, and where it’s pointing.

(OX, OY, OZ) are defined by measurements starting from the corner of the room to the camera:

- Determine the position of the camera (3,5,2)

- Determine the position of a point that the camera can see, for example (3,1,1)

- Subtract the camera point from the observed point to get the OV of the camera: (3,1,1) - (3,5,2) = (0,-4,-1)

Info

When you provide an orientation vector to Viam, Viam normalizes it to the unit sphere. Therefore if you enter (0, -4, -1), Viam stores it internally and displays it to you as (0,-0.97, -0.24).

Theta describes the angle of rotation of the camera around the calculated vector. If you are familiar with the pitch-roll-yaw system, you can think of theta as roll. If your camera is perpendicular to one of the axes of your Frame system, you can determine Theta by looking at the picture and changing the value to 0, 90, 180, or 270 until the orientation of the picture is correct.

OX, OY, OZ, and Theta together form the orientation vector which defines which direction the camera is pointing with respect to the corner of the room, as well as to what degree the camera is rotated about an axis through the center of its lens.

Gimbal lock at poles

Caution

When the OZ component of an orientation vector is very close to +1 or -1 (specifically, when abs(OZ) >= 0.9999), the orientation vector represents a gimbal-locked state, similar to pointing straight up or straight down.

In this condition, Theta values are computed using different mathematical methods than in the normal case, which can result in discontinuous behavior.

This edge case occurs because when an object is oriented nearly parallel to the Z-axis (pointing straight up or down), there is a discontinuity in how Theta is calculated. The mapping from orientation vectors to orientations remains one-to-one, but there are two well-defined regions with no smooth transition between them. This means you may see large jumps in Theta values when crossing the threshold, and eyeballing values to estimate the distance between orientations becomes unreliable near the poles.

To handle this mathematically:

- Normal case (

abs(OZ) < 0.9999): Theta is calculated using the standard method based on plane normals - Pole case (

abs(OZ) >= 0.9999): Theta is calculated using a simplified trigonometric formula to avoid mathematical singularities:- For the north pole (OZ approaching +1):

Theta = -atan2(Y', -X') - For the south pole (OZ approaching -1):

Theta = -atan2(Y', X')

- For the north pole (OZ approaching +1):

See an example of how this is handled in Viam’s RDK spatial math library.

If your application requires orientations near these poles, be aware that the computed Theta value may change significantly when crossing the pole threshold as the internal representation switches between two different calculation methods at this boundary.

Why Viam uses orientation vectors

- Easy to measure in the real world

- No protractor needed

- Rotation is pulled out as Theta which is often used independently and measured independently

Was this page helpful?

Glad to hear it! If you have any other feedback please let us know:

We're sorry about that. To help us improve, please tell us what we can do better:

Thank you!